I’m making a game that needs a lot of particles. I like to call it an “Exile-like”. I reached a point in it’s development that I really need to add some VFX to make combat feel more responsive.

A new Brackeys video on how to make VFX in Godot caught my attention. The Godot particles system is really nice. It would be great to have something like that for Bevy…

So this is what I’ve been working on for the past month or so.

What are particle systems

If you are unfamiliar, particle systems are a collection of features that allows developers to create visual effects for their games. Godot, Unity, and Unreal all have their own particle systems. Bevy doesn’t have one.

This means that we need to either rely on third-party crates, or create these effects manually. That’s how I was initially making them. But this is unfeasible for two main reasons:

- I have to create them without looking at them.

- There is no way my CPU particles would survive the constant stress test that ARPG endgames can be:

Goals

To be fair, my requirements aren’t even too crazy.

Particles must be processed on the GPU. The GPU can render hundreds of thousands of particles because it can instantiate and process them in parallel.

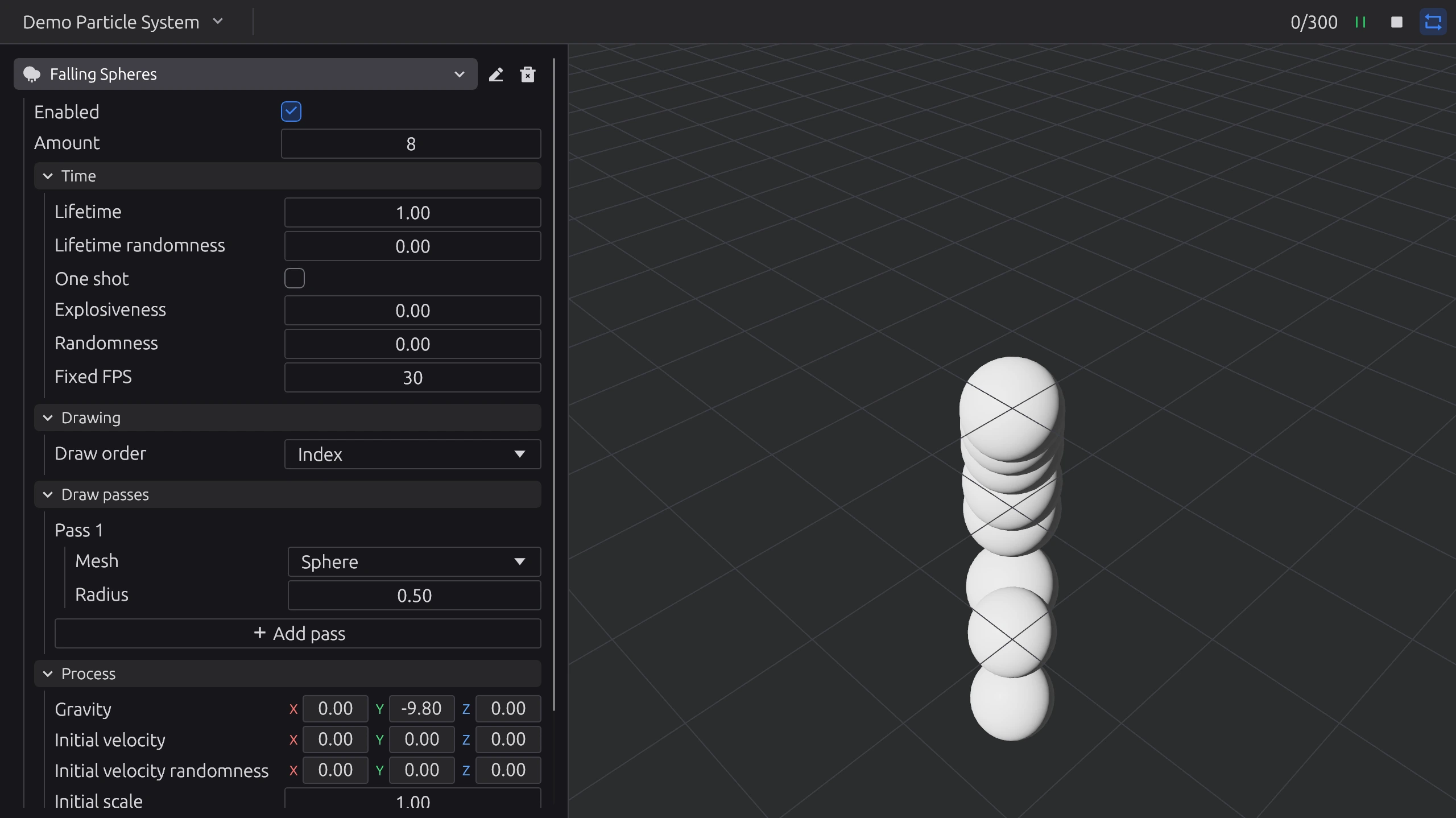

It must support 3D particles, simply because my game is 3D.

It must have a visual editor. It’s just not feasible to tweak values in a struct or text file and hope everything looks how you want them to look.

Alternatives

Hanabi is probably the most popular particle system crate for Bevy. Although it lacks a visual editor, Omagari fills that void. I tried using them both, but it was just too cumbersome for me. A combo of a counter-intuitive API and a simplistic editor.

Of course, simply using Godot itself is also an option. It already has the powerful particle system that I want. This would require migrating the entire game, something I’m either not stupid enough or too stupid to do it.

I have a thing or two to say about Godot’s particle system UX later.

Making the GPU process particles

Now let’s get our hands dirty, shall we?

At setup time, the CPU allocates three GPU storage buffers per emitter: one for particle data, one for sort indices, and one for the sorted output.

After that, the CPU only ever writes uniforms, never particle data. It never reads back particle data. It never counts active particles. It never decides which particles to spawn. All of that is the GPU’s job.

The GPU is the only one that will handle spawning, physics, collision, and rendering the particles.

The heart of the system is particle_simulate.wgsl, which handles every aspect of particle behavior. The entrypoint reads the particle data and decides whether it should spawn or update:

@compute @workgroup_size(64)

fn main(@builtin(global_invocation_id) global_id: vec3<u32>) {

let idx = global_id.x;

if (idx >= params.amount) { return; }

var p = particles[idx];

// ...

if (should_restart) {

p = spawn_particle(idx);

} else if (is_active) {

p = update_particle(p);

}

particles[idx] = p;

}The update_particle function runs the full physics update per frame:

- Age the particle and check lifetime

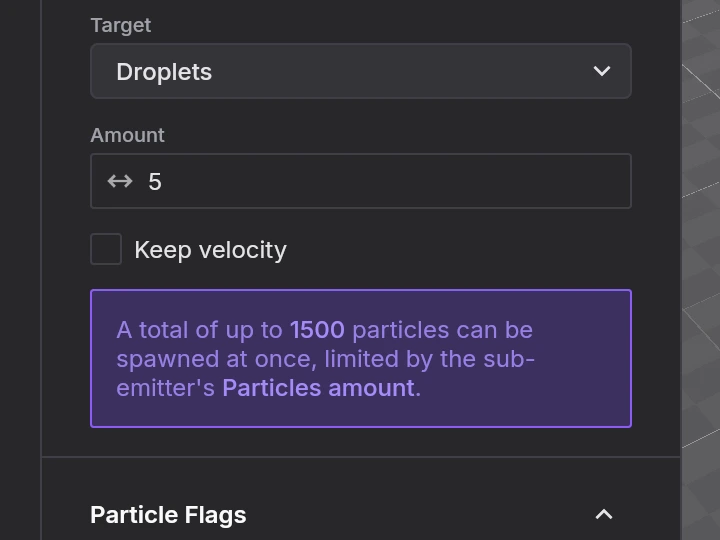

- Trigger sub-emitters

- Apply velocities & accelerations

- Apply turbulence

- Handle collisions

- And so on…

💡 Every curve and gradient is pre-baked into a 1D texture on the CPU side and sampled with a single

textureSampleLevelcall. This is not only used for color gradients, but also scale, alpha, velocity, and other curves.

Each particle gets a deterministic seed, using a multiply-xorshift integer hash function by Chris Wellons, just like Godot. Every random decision in the particle’s lifetime is derived from this seed with different offsets, so replaying the same seed produces identical results.

After simulation, particles need to be ordered so they are rendered correctly, then the render graph enforces ordering (compute runs before sorting, sorting runs before rendering):

render_graph.add_node_edge(ParticleComputeLabel, ParticleSortLabel);

render_graph.add_node_edge(ParticleSortLabel, bevy::render::graph::CameraDriverLabel);Finally, Sprinkles extends Bevy’s StandardMaterial using MaterialExtension:

#[derive(Asset, AsBindGroup, Reflect, Debug, Clone)]

pub struct ParticleMaterialExtension {

#[storage(100, read_only)]

pub sorted_particles: Handle<ShaderStorageBuffer>,

#[uniform(101)]

pub max_particles: u32,

#[uniform(102)]

pub particle_flags: u32,

}This custom material includes a vertex shader that reads each particle’s position, scale, color, and alignment from the buffer, and then transforms the mesh vertices accordingly.

It also includes a fragment shader that multiplies the particle color into the PBR material’s base color, then runs Bevy’s standard PBR lighting (or unlit) pass.

GPU instancing quirks

In Bevy, multiple instances of the same mesh with the same material are automatically instanced in a single draw call. Each vertex shader invocation gets a instance_index builtin that identifies which instance it belongs to.

This doesn’t guarantee any particular ordering, tho. And if we don’t have a “stable” mapping between the instance index and the particle data, we may see flickering or z-fighting.

Instead of instancing, Sprinkles creates a single mesh per emitter that contains every particle’s geometry “pre-duplicated”, like so:

pub(crate) fn create_particle_mesh(

config: &ParticleMesh,

particle_count: u32,

meshes: &mut Assets<Mesh>,

) -> Handle<Mesh> {

let base_mesh = create_base_mesh(config);

// ...

for particle_idx in 0..particle_count {

let base_vertex = (particle_idx as usize * vertices_per_mesh) as u32;

let particle_index_f32 = particle_idx as f32;

for i in 0..vertices_per_mesh {

positions.push(base_positions[i]);

normals.push(base_normals[i]);

uvs.push(base_uvs[i]);

uv_bs.push([particle_index_f32, 0.0]);

}

for &idx in &base_indices {

indices.push(base_vertex + idx);

}

}

// ...

}Every vertex gets the same base position, normal, and UV as the original mesh shape. But each copy also gets a UV_B (a second UV set) attribute where uv_b.x is the particle index.

From there, the vertex shader reads uv_b.x and the particle’s position, scale, color, and alignment direction from the sorted_particles storage buffer. It can then be transformed using that data.

This approach probably uses more memory than instancing would, in exchange for correctness and simplicity.

What I decided to do differently

I’m not shy to say that Godot’s particle system is a huge source of inspiration for Sprinkles, so I figured it would make sense to note what maps 1:1, where Sprinkles diverges, and why.

For starters, Sprinkles’ EmitterData covers a very similar set compared to Godot’s ParticleProcessMaterial, but organized into nested structs for readability sake, and the goal is to reach feature parity at some point.

Part of the complexity and inconvenience of Godot’s particle system is that it needs to support:

- 3D and 2D systems

- CPU and GPU systems

- Built-in processing and custom processing

- Multiple draw passes

While 2D systems may be supported in the future, much of Sprinkles’ simplicity comes from the fact that we only support GPU systems, built-in processing, and a single draw pass per emitter.

This gives me more freedom to implement each property and display them in the editor in ways that result in a better user experience overall.

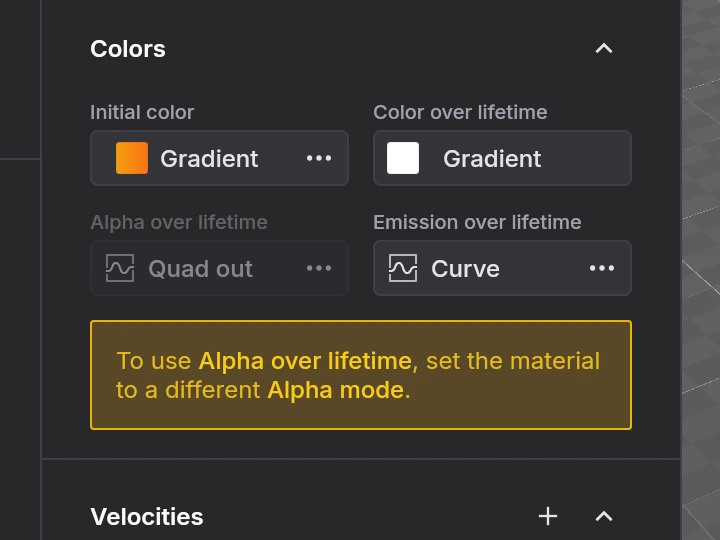

For instance, if you change alpha_curve on a Godot emitter, nothing will happen on screen. You also need to change the blend mode, which lives in a completely different place. Godot won’t tell you any of that.

Sprinkles’ editor will instead disable alpha_curve depending on the alpha mode and explain why.

Duplicating an emitter in Godot will silently share the same material between both copies. Edit one and the other changes too. You have to be mindful of which resources to share and which to instantiate.

Sprinkles editor doesn’t link these definitions, and the library instantiates identical definitions automatically.

Velocity is another one. Initial velocity is under “spawn” in ParticleProcessMaterial. Other velocity types have their own “animated velocities” section somewhere else. You just have to know where to look.

In Sprinkles everything is grouped together.

I would confidently say that the Sprinkles editor provides a better UX than Godot’s particle system inspector. And that’s not to trash talk Godot. Quite the contrary.

Many of these issues stem from Godot needing to support both the built-in ParticleProcessMaterial and custom ShaderMaterial. Since a shader can override processing entirely, some properties have to live on the emitter rather than the material. That inevitably scatters related settings across sections…

I still think the organization could be tighter though. More could be done to guide the user through how these pieces connect.

One thing Godot does get right is its in-editor documentation. I would love to bring something like that to the Sprinkles editor in the future.

The editor UI

egui is a great choice for building UI for tools. It gives you everything out of the box. The first version of the editor used it, and it worked alright, just looked ugly and lacked some polish.

Screenshot from January 22

Screenshot from January 22

If you want to customize existing widgets tho, you’re better off just implementing a new one from scratch. At that point I was fighting the framework, so I switched to native bevy_ui.

bevy_ui gives you layout, text, images, hover/press detection, and scroll. That’s it. No text inputs (I used bevy_ui_text_input for that), no event handlers, and no data binding.

Two-way sync between the UI and EmitterData became the single largest source of complexity in the editor. I built a custom FieldBinding system using Bevy’s Reflect trait for type-erased field access.

Bevy Feathers landed in 0.17, but explicitly leaves state management to the app.

BSN promises reactivity eventually™ , but the Bevy team’s vision doc from 2024 said it’s not on the near-term roadmap.

I wanted to build a particle system and had to write a UI framework. At some point I wasn’t even working on the library anymore, just debugging why a checkbox wouldn’t sync its state to a nested optional enum field.

Contributing upstream crossed my mind every time. But the gap between “I should comment on this issue/thread” and actually doing it is, for me, gigantic.

Next steps

For now, I’ll try to focus a bit more on the game I’m building, and only upgrade Sprinkles as I need to. In the end, that’s why I built it.

I do have some features in mind, specially some quality of life ones for the editor such as Ctrl/⌘ + Z, reordering emitters, and more.

2D support is planned but is not a priority for me, since I’m currently working on a 3D game.

I hope you try Sprinkles out, tell me what you think about it, and maybe even give it a star on Github!